I sit by a large tree and I am in the mood to forget myself.

It stands at the forest shores, neighbouring a green meadow that gently rolls down onto the city edges. Looking up, its heavy branches are loaded with green foliage. The leaves form a kind of roof to hide under.

The sun above casts an emerald shadow. I pick it up and press it against my chest. I check for its texture and the flow of seam as I sway from side to side. Caressing my hips and awakening spaciousness. I slip into beauty for the duration of a breath.

It occurs to me that I find myself below, above, and next to this tree. I wonder – what’s it like to be them? A gentle rustling moves through the branches, the breeze brushes up against me. Why is it so hard to take this question seriously? Why does my rational mind immediately shut out the thought, dismissing it as foolish or childish?

I remember, it used to be so simple to step into otherness as a child. To read the forest and effortlessly turn into a tree, a squirrel or a small creek. Racing past predefined ideas and concepts of what the world ought to be and how we ought to be in it. Poking my fingers into the moist mud as I drew up riddles and maps of imaginary worlds. It didn’t feel ‘other’ at all.

Where did all of that go?

I lay down right by the tree trunk. Resting my head on the gentle curves that border the above ground and the deep down under. Staring up, I can see its thick wooden crust and its cravesses. The steep wrinkles that turn into yawning valleys for the ants that run up and down. The hair on my forearms rises to meet the leafy canopy. Defying gravity.

I stretch myself further.

Further into existence.

A thought surfaces.

Are we really so different?

A sigh.

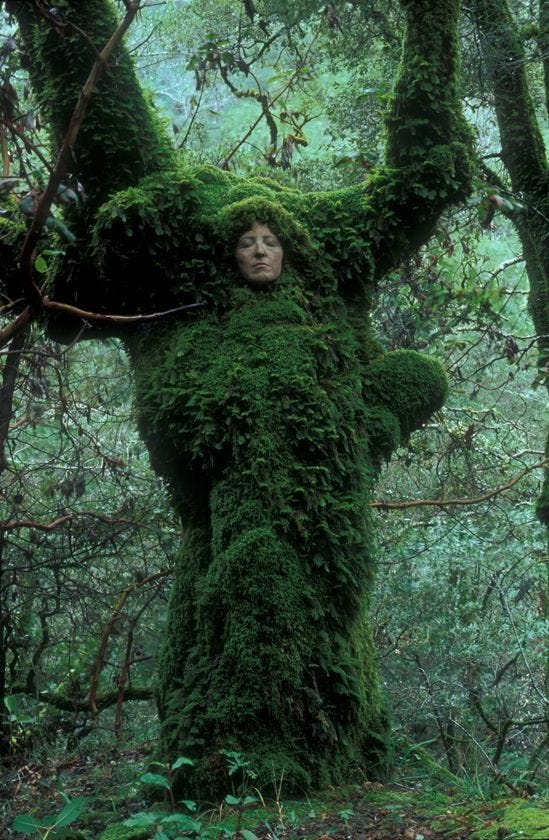

My intuition gently tugs, and asks me to look more closely. To trace the lines on our skin and bark, that tell the tales of our aliveness. To follow it all the way back to 1.5 million years ago. To when our paths split on the planes of evolution. Unravelling the common ancestry we share. Acknowledging our separateness and similarities across personhood.

The tickling steps of a beetle crawling up my forearm draw my attention. I adjust my back as I feel the embrace of the roots that dive into the ground and extend far below. I ponder on how, – if we were able to look at trees upside down – we would see that their foundations far extend the leafy crowns that reach skywards.

A tree’s root system grows wide, rather than deep. Forming thick mats in the topsoil to access oxygen and water. The roots extend towards kindred beings underground, but not only. Invisible to the human eye, they are enveloped by mycorrhizal fungi. Forming a symbiotic relationship as they stretch out their hyphae. These feathery threads that make up most fungal structures extend into vast networks beneath the forest floor.

Tying a sort of fabric of care. Connecting different trees of various ages with each added thread. This allows them to be in frequent chemical conversation. Exchanging resources and warning each other of damage or threats. Taking care of each other in times of stress and grievances.

This knowledge translates our understanding of a forest. From being but a collection of single, individual trees to an intricate system of trade, collaboration and inter-being. Passing down the raw knowledge of the seasons and circumstances between boral generations. Wisdom that is otherwise neatly tucked away into the tree thorax. Showing up in rings.

I wonder, where does this tree right here end?

Are we really so different?

Do I really stop at my skin?

Do I not recognize myself in this behaviour? Have I not felt the rupture and tears in the fabric of care that I am interwoven in? The hardships faced by the people I love. The damage faced in my extended network. It pulses in red pain and worry between us. Of course it does, it matters. Have I not felt the wound, even if it was on different levels of intensity?

Yes, we hurt together. We grieve with each other. Extending a hand.

I sense the fungal filaments span out far between us. We share the same fabric of care. Bound to one another by invisible dendritic threads, a mutual becoming-with. Sending the chemical messengers of protection and care among us. A net of aliveness that we cannot untether ourselves from.

Or as the poet Ross Gay once put it in his Book of Delights:

“Is sorrow the true wild?

And if it is — and if we join them — your wild to mine — what’s that?

For joining, too, is a kind of annihilation.

What if we joined our sorrows, I’m saying.

I’m saying: What if that is joy?”

The day we learn an old language is the day our world changes. Whether it’s the language of our emotions talking through our bodies or the bird song right outside our window. Whether it’s the way we grow around our grief or the vibrations of threads and filaments furnishing the forest floor. The moment we open ourselves up to these ways of seeing, ways of listening, is the moment our entire understanding shifts.

I get up and place my palms on the cool bark, extending a hand. Tilting my face skywards I sketch the aliveness that I’ve come to meet by the forest bank. I stand in awe of this creature that I seemingly know so little about. Tracing leaf margins and vein patterns. My gaze runs down its trunk, mapping the crust of the tree. Above my eyeline I can make out a round callus colored in shades of brown unlike the rest of the bark. I touch this cloak of softness. It holds the memory of a wound. A remnant of protecting its core and warding off further damage. A mark of growing inward and forming a tender seal.

Trees don’t heal the same way humans do. When damage occurs, trees don’t regenerate the wounded tissue directly. Instead, they compartmentalize the injury by developing specialized barriers. At first a chemical response helps to ward off invading pests that are attracted by the sugars and phytochemicals that were laid bare. The second phase is a slower mechanism of adaptation, scaring over the physical damage.

The so-called woundwood is made up of soft tissue that grows over the hurt area and seals it off. It is the slow and steady forming of four walls of cells that provide a protective barrier against the spread of disease. Preventing the decay of the entire tree and walling off the traumatic event.

The common gardener’s saying describes this process:

“Humans heal, trees seal”.

I hold that thought. I turn it over in my mind, examining its edges. Something about this falls flat, like the crashing sound of a tree trunk hitting the forest floor. It doesn’t feel entirely true. Yes, our human flesh and bones have the ability to heal after damage. Sometimes only, if we are lucky to receive the necessary care.

But when the previously unimaginable happens, our subconscious tries to keep us safe. Some things pierce through our flesh and into the bone marrow of our psyche. Some stuff we will never get over. No matter the amount of hours engaged in healing practices. But our body holds a wisdom older than the span of our single lives. Applying a survival strategy that is smarter than our individual minds. Slowly rebuilding the layers of the outer shell of our spirit. Until we can face the world again.

Maybe then, walling off is a coping mechanism we also know. Remembering the slow process of sealing the wound emotionally. Of allowing what happened to us to exist. And to grow around it. Without the need to make sense of it or to make it undone.

To live with our grief. Because we know that it will never really leave us anymore. As it transfigures, it forms and shapes us. Forming a callus in our psyche. Growing larger as we accept it as a part of us. Until it no longer poses a threat to our aliveness, to our survival. And so, we continue living.

Or in the words of the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön:

“We think that the point is to pass the test or overcome the problem, but the truth is that things don't really get solved. They come together and they fall apart. Then they come together again and fall apart again. It's just like that. The healing comes from letting there be room for all of this to happen: room for grief, for relief, for misery, for joy.”

I notice a soft pillow of moss next to my right thigh. Its potentiality shapeshifts into attention and form. Existence coming into focus. Initiating the permeable loop of acknowledging each other’s possibilities of being. The forest notices me back. In this instant our world enlarges. It draws another breath and swells with wonder. Multiplying with opportunity and connection.

I once was the falling rain and the plenitude of this forest.

I once was the minerals in the soil.

I once was the silence

that’s drawing breath

in between the cries of a red kite.

This isn’t a question of faith. This is the chronicle of life on Earth.

We participate in the same elements and matter.

We all share this instant and an ancient story.

A story so old, it pulses

through buried branching filaments.

It crackles in the thunder where

the sky meets our towering branches.

I can feel the charge of stirring clouds.

I can smell the change of air.

The winds are gathering

and awakening the orchestra

of a weighty boreal crown.

To move within these mysteries is to notice

How much we don’t understand about ourselves

Or anybody else. It is knowing,

That all that we can do, is

To tend to the fabric of care.

And to ask – every now and then:

Are we really so different?

Or in the words of the Irish poet John O’Donohue:

“You have traveled too fast over false ground;

Now your soul has come to take you back.

Take refuge in your senses, open up

To all the small miracles you rushed through.

Become inclined to watch the way of the rain

When it falls slow and free.

Imitate the habit of twilight,

Taking time to open the well of color

That fostered the brightness of day.

Draw alongside the silence of stone

Until its calmness can claim you.”

This post was inspired by Sympoiesis’ “Multi Species Worlding Workshop” that I had the chance to take part in last autumn. The Berlin-based experience and design lab was co-founded by Niels Devisscher and Rūta Žemčugovaitė. Their method is available open source (which I love) as part of the Collective Imagination Practices Toolkit.

I loved the way the article beautifully interconnected all living beings. What resonated deeply with me was the message that there is no single "correct" path to healing. In mainstream discourse, trauma is often expected to be resolved through behavioral or chemical interventions — and those who choose a different path, who suppress their pain and simply move forward, are sometimes seen as doing something wrong. But you offered a different perspective: look at the trees — it’s okay that way. Healing can take many forms, rooted in our connection to nature, our inner rhythms, and the diverse practices that speak to each of us individually.